Magic

A needle of iron, marked with the sign of the Bear-Star, will point north when floated on water. A spindle of blue agate will always point rimward.

According to Haron the Founder, a certain spiral sigil, carefully etched onto the surface of a quartz gem, will store and collect light; an ancient phrase and a gesture of the hand will cause the gem to glow like a torch.

According to Peltor of Karsis, a few words of the high speech, spoken with force of will and an understanding of the underlying formula (expressed in On the Workings of the Heavens as a complex tangle of lines and symbols) can produce a bolt of lightning from a clear sky. He also cautions that the spell is especially taxing, and that the feeble and the unready are more likely to destroy themselves than produce any real result.

According to Olcernus the Great, the blood of a living dragon, mixed with ash from the body of a dead king, quicksilver, and aqua regia, forms a vapor which obeys commands given in the high-speech, and which rapidly reduces anything it touches to ash.

Warmages serve kings and emperors in battle. Windsingers send ships safely on their way. Hedge wizards mumble over old boundary stones, and keep the night-things at bay. In every corner of the world, magic leaves its mark.

The Lineage of Alhalus

Men have wielded magic of various sorts for the whole of recorded history. The Book of Aliax says that the authority taught man magic before the fall and the breaking of the world. The mages of the Age of Heroes and the First Age of Man are the stuff of legends--they are remembered as heroes, demigods, and monsters.

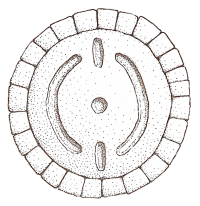

Most histories would begin instead at the dawn of the Age of Glory, with the rise of Alhalus, the navel of the world. From its rocky island, the city-state became the great power of the age, and in its great forum were found wonders from every corner of the earth. Here, the Garpriests of the great temples honored their gods and wielded powerful magics in their name.

But the priests were not alone in their pursuit of knowledge and power.

The wise men of the city found the marketplace as rich in knowledge as it was in foreign treasures. The first of the cynic-mages (from the old Heliac for "doglike") learned their tricks from poor foreigners and shoddy copies of ancient books, but where each Garpriest had a single teacher, each cynic-mage had twenty. Many of their names are lost to history, but their spells are not. Jerastos of Gor named the principle elements (along with many others less well remembered), and divided magic into two types, two ways to manipulate the elements: magic which creates and magic which alters. Aelika the Mute created a lexicon of the High Speech, which she theorized was the Divine Language.

The power of the Garpriests waned, their mysteries drained away, and the influence of the mages grew to threaten the oligarchs themselves. In the end, only exile saved the cynic-mages from slaughter.

Haron the Founder, himself a noble, built a school not far outside the city. He called it the Orchard of the Perfect Thought, though we know it as the Academy. He and his followers divided the school and the spells taught there; they named the schools of magic still used today. The school grew quickly, and its library was called the richest treasury in the world.

Amid this flourishing, Peltor of Karsis formed the first comprehensive theory of magic. He and his followers created hundreds of spells; perhaps most notable are those capable of unraveling the threads of magic. Peltor is still sometimes called the Spellbreaker. But within a generation, even the Peltorists would be overshadowed by Olcernus the Great, whose refinements and explanations of Peltor's work would make his writings the basis of all subsequent inquiry and practice.

As the age neared its end, the power of the Academy waned. It was sacked by the Hierarchs of Alhalus in the chaos that preceded the Second Age of Sorrow. Numberless works were lost in the sack; great sages preserved only by a passing mention in a surviving text. These remnants are the basis of all modern science.

Since the destruction of the Academy, further development of the art has been scattered and secretive. Aelika's ideas were more popular with the prophets of Badia than they ever were in Alhalus. They still shine through in the holy texts of the church, especially the Book of Aliax; today she is revered as St. Aelika the Mute and honored with a feast at the autumn equinox. The works of Olcernus and his followers have blended with church doctrine, truly becoming the foundational texts of most magical study.

In 554, the Academy was refounded as an imperial library, commonly called the Second Library. Though its patrons have made it an impressive repository of knowledge, it will never again be the center of learning it once was.

Theories and Traditions

Only a rare few mages advance the art at all, and these few do so because they stand upon the work of those before them. Modern sages divide magical traditions along a few great lines, and an infinity of little fissures and schisms.

First are the little-mages, those who practice magic without any real training or scholarly knowledge. They are everywhere, but generally below the attention of those who keep the secrets of ancient arcane lineages. They make do with folk wisdom passed down from generation to generation, simple magic mixed with superstition and practical experience. Rare is the Hedge Mage who is not also a bard, an apothecary, and a fortune-teller.

Next are the diverse lineages outside the greater Alhalic tradition, the ancient cults of Gossas and Sansok, the Whiteeyes of Pesh, and the Seers of Unlas. This are further divided by their age--the antediluvian and the post. That these traditions might still bear secrets from before the Drowned Age is a subject of endless doubt and speculation.

Naturally, western scholars are far better equipped to categorize themselves. Even in the west, and even after the conquest, there are innumerable renegade lineages, the products of exiles and eccentrics; these are the illegitimate lineages. Of those who accepted the Alhalic tradition, the first to set themselves apart were the Aelikans, so unorthodox in their philosophies as to be considered almost illegitimate. Several modern traditions still call themselves cynics, rejecting the exile of the mages from politics and religion, even as they generally accept without examination the teachings of the exiles. Then there are the Peltorists, less known for their particular doctrines than for the rejection of the "refinements" of Olcernus. They claim the theories of Peltor are more than sufficient in the hands of diligent students. The Peltorist traditions are generally backwards-looking; unsurprising, given that so many of Peltor's works are lost, or else survive only in critiques by Olcernus.

As for Olcernus, few traditions today would call themselves Olcernists; that term is usually reserved for the historical followers and students of the great mage. Such is the extent of his influence that to be a modern Olcernist is almost without meaning.

No Comments